‘Geopolitics is notoriously difficult to predict even with the collective wisdom of the markets so I wouldn’t expect markets to price that in ahead of time,’ said Michael Reynolds, vice president of investment strategy at Glenmede.

The Israel-Hamas conflict has the potential to draw in other countries and boost oil prices in a way that could unhinge inflation expectations.

MARKETWATCH PHOTO ILLUSTRATION/ISTOCKPHOTO

Intensifying conflict in the Middle East, stemming from Israel’s war on Hamas, is giving rise to concerns by traders and investors about the possibility of a second wave in U.S. inflation that hasn’t been fully factored into the financial market.

Oil prices settled almost 6% higher on Friday, or by more than the moves seen on Monday, amid fears of a ground assault on Gaza by Israel. Investors flocked to safety of long-dated U.S. government debt for the third time in the past week, and U.S. stocks finished mostly lower on Friday. However, inflation traders largely stuck by their previous expectations for the annual headline rate of the U.S. consumer-price index to stay between 3%-3.6% each month through next March.

Market participants are focused on the risk that the war could draw in major oil-producing countries in the region such as Saudi Arabia and Iran, which might reignite U.S. inflation. In assessing the outlook, inflation traders said they’re taking their cues from volatile energy prices and not the conflict itself yet, while others appear to be in a wait-and-see mode. The International Monetary Fund remains prepared for the possibility that the conflict puts upward pressure on inflation, and European Central Bank policy maker Klaas Knot is keeping an eye on any impact for the eurozone.

“It’s hard to imagine a scenario where it’s deflationary, that’s for sure. The question is just how inflationary it is,” said Michael Reynolds, vice president of investment strategy at Glenmede, which oversees $42 billion in assets from Philadelphia. “If we maintain the status quo now of limited conflict, it may not be materially inflationary. But if it escalates to the point where major oil-producing countries in the region start to get directly involved, that’s where the big upside risk to inflation lies.”

Moreover, “geopolitics is notoriously difficult to predict even with the collective wisdom of the markets so I wouldn’t expect markets to price that in ahead of time. The market is looking at this with a really clear head and is likely going to be pretty reactive,” Reynolds said via phone, adding that Glenmede is currently overweight on cash and fixed income, while underweight on equities. “The inflation outlook in the market has been priced to perfection, with a straight line down to the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. From our perspective, that’s a Goldilocks scenario that doesn’t leave room for shocks, and one should throw all those plans out the window now.”

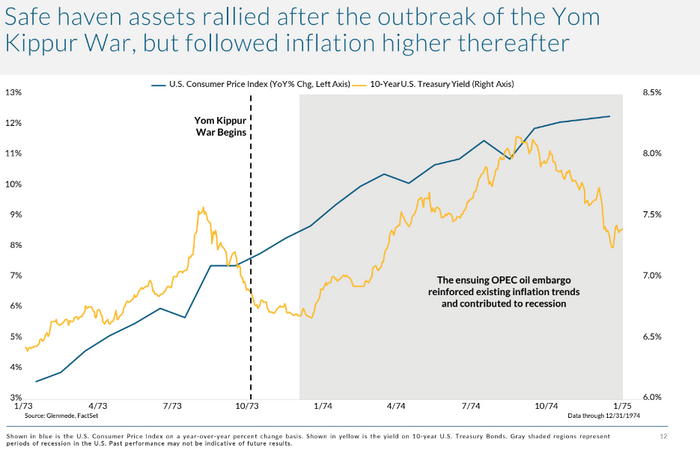

History provides some guide about the possible trajectory that markets and inflation might take following the outbreak of a war in the Middle East. After the Yom Kippur War of 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria, U.S. government debt rallied for a few months on its safe-haven status, pushing the 10-year yield below 7%.

But inflation, as measured by the year-on-year change in the U.S. consumer price index, kept moving mostly higher for more than a year after the 1973 war, an event that led to the 1973-1974 oil embargo. The embargo banned petroleum exports to targeted nations, including the U.S., and introduced cuts in oil production. It was only a matter of time before Treasurys sold off again, as they did before the war — sending the 10-year yield above 8% and heading in the same direction as annual headline CPI inflation in 1974.

SOURCE: GLENMEDE, FACTSET. CHART SHOWS YEAR-OVER-YEAR CHANGES IN THE CONSUMER PRICE INDEX, ALONGSIDE THE DIRECTION OF THE 10-YEAR TREASURY YIELD FROM JANUARY 1973 TO JANUARY 1975.

In addition, the S&P 500 SPX struggled to return to its pre-1973 levels for years after it became increasingly clear that U.S. inflation was spiraling out of control after the Arab oil embargo.

As geopolitics reared its head over the past week, Dow industrials and the S&P 500 managed to score weekly gains of 0.8% and 0.5%, respectively, on Friday despite concerns about the war. However, the stock market’s expectations for volatility VIX jumped to almost where they were on Oct. 3, when the higher-for-longer theme in U.S. interest rates pushed the 30-year bond yield to a 16-year high.

Markets also pulled back a bit from recent moves which had been fueled by U.S. economic resilience and persistent inflation. Those earlier moves had involved traders boosting the likelihood of a December interest rate hike by the Federal Reserve, pushing the dollar to its highest levels in 20 years, and sending long-term Treasury yields into multiyear highs.

“So where do things go from here? With geopolitical risks building by the day, that’s a difficult question to answer,” said James Rossiter, head of global macro strategy for TD Securities in London.

Oil prices won’t likely stress central bankers too much unless they lead to higher long-term inflation expectations, and it would take $140-per-barrel levels to push headline U.S. inflation to 5% later this year, Rossiter said. Via phone, the strategist said “we’re not really taking a strong view one way or another.”

“Certainly there are concerns about upside risks to oil prices,” he said. “If things really do escalate rapidly and other countries are brought in, it’s fair to say that $140/barrel oil may be well within sight. We’re not ruling that out, but we don’t have quite enough information. Ultimately, there’s a whole range of outcomes we could have and we would be more concerned about how oil price shocks may feed into inflation expectations.”

Data released on Thursday underscores how difficult it’s been to get U.S. inflation back down to 2%, with the consumer price index for September showing the annual headline rate failing to move below 3% after four straight months and the narrower monthly core measure not budging much.

“Oil has to be a major concern,” said John Farawell, executive vice president and head of municipal trading at New York bond underwriter Roosevelt & Cross. “I see a lot of uncertainty,” he said via phone, adding that the bar for getting to a second wave of U.S. inflation has gotten easier and puts the Federal Reserve in a bit of a dilemma.

A long line of Fed policy makers are set to speak during the coming week, ahead of the media blackout period which leads up to the central bank’s Oct. 31-Nov. 1 meeting.

Monday brings the New York Empire State manufacturing survey and two appearances by Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker.

On Tuesday, data is released on U.S. September retail sales, industrial production, and capacity utilization, as well as business inventories for August and October’s home builder confidence index. Fed Gov. Michelle Bowman, Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin, and Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari are also set to speak.

Wednesday brings September data on housing starts and building permits, along with the Fed’s Beige Book report. Fed Govs. Chris Waller and Lisa Cook, as well as New York Fed President John Williams, are set to make appearances.

Weekly initial jobless claims are released on Thursday. Other data includes the Philadelphia Fed’s manufacturing survey for October and September’s existing home sales and leading economic indicators. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee, Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr, and Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic are all due to give remarks.

Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester is set to speak on Friday.

Original Source: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/treasurys-weird-security-approaches-5-yield-signaling-10-year-rate-may-too-197b4c94?mod=vivien-lou-chen